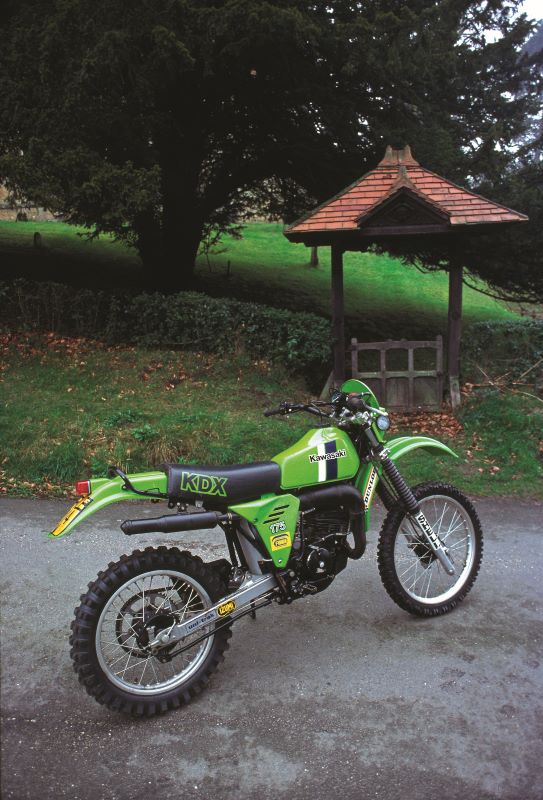

In the enduro world smaller is often better, especially if it has a superb rear suspension like Kawasaki’s Uni-Trak system.

Words: Tim Britton Media Ltd

Pics: Mortons Archive

Keeping the rear wheel in contact with the ground has long been viewed as a way to win races. Yes it’s very spectacular when MXers leap hundreds of feet in the air and do fancy loops but if you’re in the air, you’re going nowhere. Once the idea rear suspension was a good thing for off-road motorcycles caught on, the battle was under way to make it work as well as it could.

Most suspension in the early days involved a fork generally known as a swinging arm pivoting on a spindle behind the engine and two hydraulic units connecting either side of the rear wheel spindle end of the fork to the frame. For years this was enough, people played with spring-rates and manufacturers experimented with unit length but in the main things stayed pretty much the same for all of the Fifties and well into the Sixties.

When the scrambles world became the MX world and the European factories took over from the British factories then there was experimentation with damper position to provide maximum travel for the wheel. Shock units were angled at the top or moved up the swinging arm at the bottom, then back again as makers battled in the early skirmishes of the suspension wars where the goal was to make their team bike faster and easier to ride but the bikes still had a pair of shock absorbers at the rear. Now, not every manufacturer in motorcycling history was so tied to convention and there are quite a few examples of makers for whom two shocks at the rear of a motorcycle didn’t sit right. Vincent HRD was one such company which embraced a cantilever system which had the two shocks mounted under the seat. BSA went a stage further and created a monoshock rear end for a C15 trials bike but it took the cut and thrust of the Japanese-influenced race scene in the Seventies to bring about the next revolution in rear suspension – the cantilever monoshock. We talk more about this system in issue 67, suffice to say when it appeared it put everyone else on the back foot, be it technologically or aesthetically.

Enjoy more articles like this one with a subscription to Classic Dirt Bike. Check out our current subscription offers here.

This cantilever system wasn’t the be-all and end-all, it did suffer from overheating of the suspension unit, something which Yamaha addressed for the YZ465 and made some improvements. Elsewhere in Japan a new system was being developed and this was to take the suspension battle to greater heights… the colour on the tank was green, the name Kawasaki… the system Uni-Trak and what a step up this Uni-Trak was.

At once it ensured the rear shock ran cooler because it was out in the breeze rather than stuffed up under a petrol tank. Its movement matched the travel of the rear spindle and kept everything in line and it used a linkage to connect the damper unit to the swinging arm. Once this system was allied with a smaller bike Kawasaki had a serious challenger to Suzuki’s PE175.

To recap a little, the idea that a smaller, more easily handled motorcycle might be the way forward for off-road sport gained quite a bit of ground in the Fifties in the UK. It didn’t hurt the idea when reports of the ISDT – pretty much the only enduro-style event reported in the UK press – contained images of foreign teams with tiny motorcycles, generally under 250cc, doing most of the winning. Even the UK teams cottoned on to the basics when, in order to fulfil obligations to field motorcycles in the 501cc to 750cc class in the ISDT, 500cc engines were bored 40thou oversize and the resultant capacity increase to just over 504cc met the regulations and did it with a bike weighing closer to 300lb than 400lb.

Kawasaki took its 125cc MXer chassis and had a look at it; yes, thought the tech bods, the 175 two-stroke motor will slot in there nicely. While they were at it they decided an enduro bike was likely to be better cooled than the MXer so didn’t add the remote reservoir to the KDX suspension unit as they reckoned it wasn’t needed. Also not needed, according to contemporary tests, was any road-legal equipment.

–

Uni-Trak keeps Kwak on track

Since the idea that the rear of a motorcycle going up and down would make life a bit better for off-road motorcycles and their riders caught on with manufacturers, their technical departments have been working tirelessly to ensure their motorcycles have the best possible suspension system. Kawasaki adverts described the Uni-Trak system as ‘Power to the Ground’ and maintained the not-unreasonable view of ‘if a bike’s rear wheel is in contact with the ground more, then the rider will go faster.’ The Uni-Trak system tackled the big bugbear of monoshock suspension – extra weight too high up – by positioning the shock beneath the rider and connecting it to the swinging arm by a rocker linkage. With the shock in this position it works in the same plane as the rear wheel so gives a smoother action and benefits from being much more exposed to cooling air than, say, a shock mounted under the petrol tank.

–

One set of testers went as far as to say, as road legality is a subjective question where dirt bikes are concerned, Kawasaki had sidestepped the whole issue and provided a totally off-road motorcycle which could, should the owner wish, be made road legal by seeking out various items from Kawasaki’s other motorcycles. What was needed was a metal rather than plastic petrol tank, a chain guard and a stop-light switch plus a speedometer rather than just an odometer. The chain guard was a puzzling omission as even in a few hours on a test track the gearbox sprocket ended up being packed with mud, something an even minimal chain guard would, if not prevent, certainly lessen. It is possible to understand the lack of a speedometer as for an enduro competition an odometer is of more use and these days – we’re talking 2023 – the vast majority of enduros don’t include any roadwork so a speedo isn’t really needed but in 1980 more events had a short stretch of highway. As for the plastic petrol tank, this wasn’t just limited to Kawasaki as just about every dirt bike imported into the UK had to have a metal tank made by the importer. The reason for this harks back to the Sixties and the café racer customising craze. There were in those days lots of responsible manufacturers of such accessories who produced high-quality products but there were a lot of less reputable outfits shoving out cheap and nasty stuff which barely held petrol and if involved in an accident these crap tanks would explode. Of the many things to do with five gallons of premium petrol, having it blow up as you’re leaning across the container is the least desirable. The UK Government didn’t distinguish between good, bad or indifferent products but banned the lot.

These issues aside, the KDX won a lot of friends in the off-road world mainly because it worked despite its spec, which seemed wrong on paper…enduros aren’t ridden on paper though, they’re ridden on the rough terrain of whatever country the rider lives in. Thanks to the Uni-Trak suspension’s space requirements the swinging arm was much longer than the opposition models. This meant the wheelbase was much longer too; in order to make sure the bike wasn’t so long it wouldn’t go round corners, Kawasaki tucked the front end in. Yet the bike works and anyone getting out of shape in an enduro on a KDX must have done something really silly.

Kawasaki’s new-for-1980 KDX had other interesting features which were noteworthy in contemporary tests. Traditionally alloy cylinders had a liner pressed in but a liner of cast steel or iron is heavy so Kawasaki used a process where an iron molybdenum coating was blasted on and the result honed to size. It doesn’t wear very easily thanks to the amazing properties of this molybdenum but in order to keep engine compression good then piston rings need an eye kept on them.

Though Kawasaki used the 125 A5 MX model as inspiration for the KDX chassis – and the KLX 250 four-stroke version too – it wasn’t exactly the same. The dimensions were close enough to be classed the same but the long swinging arm in the MX version was aluminium whereas the KDX had its made from steel. Was this because Kawasaki was concerned an enduro event might be longer than a typical scramble and there might be bigger gaps between service checking or perhaps the company just felt the steel swinging arm was tougher for the application. Up at the front were 36mm diameter forks which were again similar to the MX model with 10in of travel but lacked the air caps of the KX125. These could be retro-fitted at extra cost so perhaps it was a cost-saving exercise to ensure the on-sale price was at or below the opposition.

One thing which was noted on the KDX was how slim and low the bike was. With no need for a subframe to keep the top damper mount in place the whole rear end was able to be much narrower. Again thanks to the positioning of the Uni-Trak the seat can be lower than the opposition; though rated at 37in high in the spec it was possible to lower it without compromising wheel travel. This helped the rider remain seated through as much of an enduro as possible which was great for the faster sections of a course. There is always a trade-off for one benefit and in this case it was the knee-steering which suffered. By this we mean being able to stand up in nadgery sections and steer the bike by gripping the tank with the knees, like a trials bike really. In practice this trade-off wasn’t a major loss as the bike handled well enough in the seating position.

Given the frantic nature of off-road racing the tiny brakes at either end of the KDX didn’t initially inspire tester confidence but while not coming in for high praise they were at least competent stoppers. Also coming in for praise was the feel of the motorcycle, by which we mean does it feel light or heavy. We’ve all experienced bikes which are technically as light as light things can possibly be but what weight there is isn’t in the right places and the bike feels heavy. For the KDX175 tipping the scales at 228lb complete with a gallon of petrol it was heavier than the opposition but on the go it felt light and this does inspire confidence when barrelling over the rough stuff.

All in all the KDX175 was viewed as a decent machine which would be popular with the club riders of the day. Its motor would appeal to those riders who liked a peaky motor needing to be kept on the boil and there were few real issues to keep an eye on. The airbox for instance was snugly fitted into quite a small space and it was felt the motor might struggle to breathe and its Yellow Peril Suzuki PE oppo had a much larger airbox for those times when the throttle was at the wide open end of the cable and gulped a lot of air. There were concerns too over the waterproofing for the airbox which was okay on the contemporary test but what would it be like in the Welsh bogs of the Welsh Three Day or the ISCA perhaps.

In the three-year lifespan of the model there were a few improvements from this first year KDX175 to the last version. An ongoing theme was linkage bearing lubrication; it wasn’t difficult but didn’t get done often enough by enthusiasts. The bearings would take a while to fail but without attention, fail is what they would do. Each version of the bike carried the ‘must lube linkage bearings’ warning, if not literally then certainly figuratively.

First change to the model was when Kawasaki fitted air caps to the forks for the A2 model then when the last version came in the gear cluster had altered ratios to close the gaps in several of the ratios. So, not a totally perfect machine but one which encouraged owners to use the 24bhp to the full and squeeze maximum enjoyment out of every single bhp!

If you enjoyed this, we think you’ll like…

- The Unreported 1980 Scottish Six Day Trial

- Lightweight Performer: A history of BSA’s Bantam

- 1974 Kawasaki MX – Lean, Mean and Lime Green

Kawasaki 1980 KDX 175

Engine: Two-stroke single

Capacity: 173cc

Bore x stroke: 66mm x 50.6mm

Frame: Single tube cradle

Forks: Leading axle oil-damped telescopic

Rear suspension: Single oil-damped unit

Wheel F: 3.00in x 21in

Wheel R: 4.00in x 18in

Brake F: 4.7in drum

Brake R: 5.1in drum

Wheelbase: 57.5in

Ground clearance: 12.5in

Weight: 218lb